Administration and Maintenance¶

In this part, we will give more insights on details of the components of CVault. This is necessary to understand and troubleshot funky behaviors in order to fix them.

Data Exchange¶

In a client-server distributed system, the data exchange issues lay at the center of the overall infrastructure. For a full understanding of what is happening behind the scene, we discuss in the following of the data representation and the different protocols insuring their exchanges between all entities of the CI.

Atomic Transactions¶

The communications between each part of the CI are based upon the concept of atomic transaction. As atomic, it is the smallest chunk of data exchanged at once. Since they are to be transmitted via UX socket, they can’t exceed the smallest atomic packet size the OS kernel can handle. This max. size is set to 4096 bytes (OpenBSD kernel smallest constraint).

As shown in the picture, a transaction has three main parts:

- A query id. It tells the peer what action we want it to perform (and tells back to the sender what action has been proceeded).

- A flag giving indication on the transaction. In the response it contains the return code (standard 0 in case of success, negative in case of failure, positive if there is a particular message).

- A buffer of strings. These strings give the arguments necessary to perform the action. At return they give the responses after completion of the action. The buffer of an atomic transaction can currently store up to 16 strings, with a total size limit of somewhat 4000 bytes.

On UX socket, since we are obviously within a single machine, these transactions are transmitted almost “as is” in binary format. Over the wire, however, we must perform some kind of translation on it to become byte-ordering agnostic.

When running the Cache Manager or the Admin Daemon in foreground (switch -f), they enter a kind of debug mode where all transactions are detailed in stderr on the terminal. The following gives an example of how such a debugged transaction looks like:

atomtxn: 0x7fd35a26f7a8

id: 19

= cvcm::SEC_INIT

= cvad::ER_USR_GETA

flagrc: 0

nstrs: 2

buffer: 0x7fd35a26f7c0

g: 0x7fd35a26f7ca

str: 0x149fa80

str[0]: 0x7fd35a26f7c0

: 'cvquery'

str[1]: 0x7fd35a26f7c8

:'0'

The meanings are almost self explaining. The “g” parameter is the address of the free area within the buffer. Its value should always be:

Note that if the strings are effectively stored within the atomic transaction, the table “str” however is stored outside the transaction. Indeed, this table is not transmitted: the protocol rebuilds this table within the peer’s memory space, and the number of extracted strings is compared to the transmitted value of nstrs. Some additional checks ensure that the number of strings sent and received are aligned with the amount expected for the given transaction id.

Depending on the nature of the transaction, defined by the query ID, the buffer may be fully encrypted or not. Additionally, atomic transactions may be enabled locally or remotely. They also may be part of an overall secure, batch or sessionless transaction, according to the protocol used to transmit them.

Transactions based protocols¶

The sessionless transaction is the most simple protocol: a client sends an atomic transaction, waits for the response (or times out) and closes the connection. Some of them may be cascaded to all other cache managers, thus avoiding to repeat fastidiously the same command when we want it to operate on the whole CI at once. For example, to ask all cache managers to cleanup their cache (after a DB update for example) we just need to ask our local cvcm to perform this action and forward it to all others:

cvault$ cvctl -T -c

TRASHCACHE Ok.

cvault$

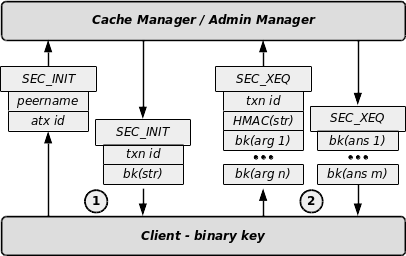

The secure transaction protocol is a little bit more complex. It is only accessible to the clients binaries registered (with the command cvcm -s) or to clients using remotely a pre-registered Client Unique ID with its key. As suggested at the picture below, it is a two-steps protocol:

- The client sends a SEC_INIT query with its name (locally as registered in the cache manager’s keystore or remotely as defined in the DB) and the ID of the action he wants to run. The server answers with a transaction ID and a challenge. The challenge consists of an arbitrary string encrypted with the registered client’s binary key.

- The client sends then a SEC_XEQ query, with the transaction id, the answer to the challenge and the encrypted arguments. The answer of the challenge is the HMAC of the arbitrary string. If the client binary key is correct, then it was able to decrypt the challenge and recompute on the cleartext the HMAC. If the challenge answer and the transaction id are correct, the server will send the results of the query encrypted with the client’s binary key. On UDP wire, however, the client must present a valid Client Unique Identifier and uses its related key. The combination cliuuid/key is stored in the DB.

The last and most complex protocol is the serialized atomic transactions or batch queries protocol. There are some cases where the return values of a query don’t fit within a single atomic transaction. In such cases the return values are serialized across a set of several atomic transactions, or - from another point of view - the atomic transactions are embedded within a batch. There is no limit in the number of atomic transactions within a batch: the amount of data transferred in an answer may be of arbitrary size. The data is to be considered as a table of size rows and rowlen columns. The only constraint is that at least one full row must fit within an atomic transaction, limiting therefore the table to 16 columns.

The picture shows the detail of this multiple steps protocol:

- The client sends a query with its arguments.

- The server answers with the flag announcing a batch: the returned values give the size of the table being returned. This allows the client to perform beforehand any necessary memory reservation.

- The client enters then a loop: it asks for the next data with a flag requesting the next bunch of values. The server sends an atomic query with the flag announcing that the batch continues.

- The server closes the batch with the last atomic transaction having the flag set to 0 (success). The client closes the transactions.

Note that when dealing with some confidential data, the serialized atomic transactions may also be used within a secure transaction. In this case, the batch is opened after the client authentication. All data are then encrypted with the key of the client.

Sessions with the Admin Daemon¶

The admin daemon cvad uses the same data representation as the cache manager. The communications occur only over a TCP wire. However, cvad is able to handle only one administration session at a time for normal operation. An edge session is available though with very limited capabilities (killing the main session, shutdown and restart basically). With cvad, there is no notion of secure transaction because all communications are encrypted with the peer key. Opening a session with cvad is a two-step process:

- The client get authenticated with its binary key the same way as for a secure transaction.

- Then, an administrator user may log in with username-password based credentials.

On a DB file, the administrator user entries have the following format:

adusers = <admin username>; MKHMAC(admin password)

For the binaries “signed” into cvcm, there is no issue. But cvad is supposed to be operated remotely as well by any application understanding its protocol. Since we don’t want to store a whole bunch of binary keys within the keystore of the cache manager, we introduced the concept of administrator clients. These clients are identified with a unique client id or cliuuid and a given client key. They have to be declared either in a special file managed by cvad or be stored within the DB.

Thus, to be able to open a session (starting with admin user login), the client binary must either use its own binary key if it is registered locally to the cache manager, or use one of the (shared) cliuuid keys. For the small Java CvAdmin application, a local file containing the credentials “cliuuid/binkey” must be defined on every host where it will be used.

On a DB file, the entries have the following format:

adclient = <cliuuid>; MK(binary key)

They can be inserted into the DB using cvctl as follow:

cvctl -z cliuuid,MK(binary key)

Troubleshooting Cache Manager¶

Many features accessible to the users or the manager involves a bulk of several different transactions with the cache manager: if one fails, then the whole feature will end up with a failure notification, more or less detailed (yes: here is room for improvements). The purpose of this chapter is to describe how features are implemented and how to pin them step-by-step in a kind of failure chasing session.

Cache Manager Inside¶

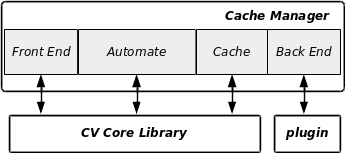

We start with a small insight of cvcm internals, illustrated by the picture below. The cache manager cvcm is a four layer binary:

- The front-end handles all incoming connections and acts as RPC receiver. After filtering out badly formed transactions, it passes the right ones to the next layer.

- The automate is responsible of the “intelligence” of cvcm. It implements call-backs dedicated to the processing of a transaction and may build and send itself some queries to its peer. It then pack the responses of the sub-layer into an atomic transaction.

- The cache stores the previous DB fetching results for obvious performance reasons. From this lower level on, there is no concept of atomic transactions any more in the data manipulated.

- The back-end is the low-level interface to the database. It is also responsible to manage the connections pool. It presents the upper layers an abstracted API to handle data in the database.

- The plugin is a specific implementation of each abstracted DB calls. At this low level, it has received a connection handler and interferes directly with the database. The targets currently are DB flat file, LDAP, MySQL and PostgreSQL. This plugin performs only 2 write accesses to the DB: one which fully destroys the DB (and rebuilds the underlying structure), and one which inserts/updates the timestamp of the cvcm currently connected to the DB.

Each layer has its own logging features, which can be easily sorted out in the log file: the main source of information for troubleshooting.

The second important source of troubleshooting informations is the set of the atomic transactions that cvcm can handle and in which circumstances. The CLI programs cvtools and cvctl presented in the next section provides all of this helpers.

Troubleshooting with cvctl¶

All examples shown in this section have been worked out on the sample DB generated by the script dbinits.ksh.

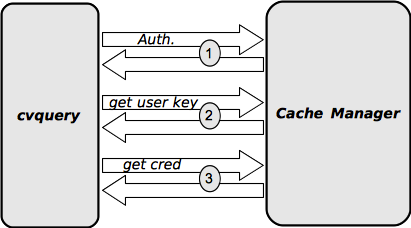

The figure below summarizes the dynamics of a credential retrieval. As explained previously, for secure transaction the client must authenticate itself with its binary key. The second step will be to retrieve the user key. Since this key is encrypted with the Master Key in the DB, the cache manager will first decrypt it and re-encrypt it with the binary key of the client before transmitting it. The third step is the credential retrieval itself. The cache manager checks the query against the ACL and if it is Ok, then its gives the credential as is. Since it is encrypted with one of the user key (hopefully the user key retrieved at the previous step), the cache manager can’t proceed to any decryption: the client cvquery here, will have to decrypt the credentials by itself.

Should the key not be the right one, then the result of the local decryption will very unlikely give a printable string:

$ cvquery -f -k 2 UXusr_ UX PROD

?55]9

$

If there are lot of keys used to encrypt the credentials, then it may become fastidious to try each of them: cvctl can help (we need the password of the admin user on cvad):

$ cvctl -g UXusr_ UX

cvmgr password: ****

0.

$

This credentials seems to have been encrypted with the key #0, and we can try:

$ cvquery -f -k 0 UXusr_ UX

usr_

$

If the ACL doesn’t allow the retrieval of the given credential, then we would get the following:

$ cvctl -g UXusr_prod UX PROD

No credential returned from Cache manager.

And the logs of cvcm shows:

RET_CRED | dom->UXusr_prod/UX[PROD], from DB:Denied

We now can list what is in the cache:

$ cvctl -l

-'crd': 2 record(s)

- UXusr__UX_; 80; ieCNBS3tkZPZkbv1E9Ps9PK3k2IF; 20150628:22:29:31;

- UXusr_prod_UX_PROD; 0; qkDOy2qeue1umBh5Toc2kS//1NdeW70lMA==; 20150628:22:29:57;

-'acl': 1 record(s)

- 80_dom; 80; 20371231:00:00:00; 20150628:22:29:31;

-'key': 5 record(s)

- 2; yAhy+Tspe9r1OyYC/e260j9dtNDFCK7K; 20150628:22:29:20;

- 4; 6Vjz7zymjUhXR4eHomleNsMs1147K5uI; 20150628:22:29:33;

- 3; ODOjORpP9VsZ8zCJHG4mGVcIDqh8Ain+; 20150628:22:29:34;

- 1; sx34aGlr8+gOBpJinzDDF9wnZ4AWh6RW; 20150628:22:29:34;

- 0; 9qPW77VhhkZ+o6pSFsX5HeDAePY6Df+3; 20150628:22:29:34;

DUMPCACHE Ok.

$

Here, we can notice that even if the access was denied, the credential has still be cached. All the keys are currently cached, because cvctl has called them all to guess the encrypting one.

If an administrator is logged into cvad to perform managing tasks which modify the DB, it is possible to ask cvad for this information:

$ cvctl -w

cvmgr password: *****

Main Session Client: 00000000

Main Session User: cvmgr

$

To get a list of cache managers currently active in the CI and their DB access status:

$ cvctl -L

1 Registered Cache Managers

----------------------------

hostreq-01 - 192.168.2.220 - 7777 - 2015-06-29 00:05:13 - DB released

$

Troubleshooting & hacking with “cvtools”¶

Since cvtools is a very dangerous utility, it is wise to use it in a development environment only. Here again, all examples shown in this section have been worked out on the sample DB generated by the script dbinits.ksh.

Using cvtools, we can by-pass the admin user authentication since this tool can act on behalf on any registered client. This utility can be used to send any hand-crafted atomic transactions to cvad and to cvcm and perform some cryptographic operations as well. Due to absolutely no check against the validation of the transactions it sends and of the answers it receives, cvtools may generously end up with SIGSEV and friends.

“Single Step” insight in the transactions between clients and servers¶

As an example, we will synthesize cvquery in the operations retrieving a credentials. It is a 3 steps process. First, we get the credential:

$ cvtools -t cm -k cvad -q RET_CRED,dom,UXusr_,UX,% -s

ieCNBS3tkZPZkbv1E9Ps9PK3k2IF

Some remarks:

- Since this transaction is supported by the cache manager, we instruct cvtools to target it with the switch “

-t cm“ - The sign “

%” is used to mark the empty string in the arguments list. We choosed this sign because it interferes very little with the shell command line, allowing the user to spare escape sequences when passing empty strings. - We also added a “

-s” because we face here a secure query, for which we must use the particular authentication protocol described previously. - Since a client must authenticate with its registered binary key for such transactions - and cvtools is NOT registered (and can’t be) - we have to instruct it to “still” and use the key of a registered client: this is achieved with the argument “

-k cvad”.

To continue with the second step of credential retrieving, we call the user key encrypting this credential (as illustration, we use now the binary key of cvctl):

$ cvtools -t cm -k cvctl -q GET_USRKEY,0 -s

UsrKey0

Then, we decrypt the credential with the given key:

$ cvtools -z UsrKey0,ieCNBS3tkZPZkbv1E9Ps9PK3k2IF

usr_

As a second example, let’s synthesize the cache managers list command of cvctl we met in the previous section. This query starts first by asking the local cache manager for its registered peers, and then by asking every one for its DB status:

$ cvctl -L

2 Registered Cache Managers

----------------------------

reqhost01 - 192.168.2.220 - 7777 - 2015-07-01 23:31:46 - DB released

reqhost02 - 192.168.2.102 - 7777 - 2015-07-01 23:29:11 - DB released

To synthesize this query, we first get the list from the local cache manager:

$ cvtools -t cm -k cvctl -q LS_MGRS -b

data 4 x 2 record(s)

- reqhost01; 192.168.2.220; 7777; 2015-07-01 23:35:43;

- reqhost02; 192.168.2.102; 7777; 2015-07-01 23:29:11;

The switch “-b” informs cvtools that we face here a serialized transaction and that we want to follow the batch to get all data returned. Without it, cvtools just shows the data geometry (the first atomic transaction returned, see batch queries exposed sooner).

Then, for each cache manager, we ask for its DB status:

$ dom$ cvtools -t cm -h reqhost02 -p 7777 -k cvctl -q HANGUPSTATUS -u

DB released

$ dom$ cvtools -t cm -h reqhost01 -p 7777 -k cvctl -q HANGUPSTATUS -u

DB released

The switch “-u” dictates cvtools to use the UDP protocol to communicate with the target. The host must be obviously named and it is the purpose of the switch “-h”. The switch “-p” gives the UDP port to address.

Note that the later transaction could be addressed directly to the local cache manager since the query runs from this host (check the previous timestamps :-)) and cvtools uses UX sockets as default channel:

$ dom$ cvtools -t cm -k cvctl -q HANGUPSTATUS

DB released

Those two examples show how it is possible with cvtools to execute each single atomic transaction, part (or not!) of any more complex queries, which run within the CI. In the next section we will go more in details on cvtools capabilities.

Cryptographic capabilities¶

In short, cvtools can synthesize directly or not every cryptographic operation used in the CI.

- To decrypt with a user key, use the “

-z” switch. Encryption is accessible as standard feature of cvquery. - To decrypt/encrypt with the client stolen key, use “

-C” (ciphertext) and “-P” (plaintext) switches. - To perform one of the 3 Master Key related operations (encryption, decryption, HMAC), still the key of one of the “mkprivilege” declared clients in the cache manager configuration file and run the corresponding MK_REMOP secure transaction on cvcm. If cvcm is not running, Masterkey cryptography is not available (if the user running cvtools has the binkey of cvcm to start it up, then she can access directly to Masterkey cryptography via cvcm native features).

Atomic transactions synthesis¶

Before trying to synthesize any atomic transaction, one must know which ones the daemons are able to handle and how do they operate. cvtools provides a regex based search for help. For example, we can try to learn about queries with the name “CRED” as the following:

$ cvtools -S CRED

cache: RET_CRED; 0; < 4 = 1 >; no forward; shared; ux; secure

admin: ERU_GETCREDROW; 22; < 3 = 3 >

$

RET_CRED which we already know is targeting the cache manager, has the ID 0, needs 4 arguments (first number), sends 1 return value (second number), is not forwardable to others, is shared (or not exclusive, meaning that cvcm can process it concurrently with others in parallel), is available on the UX socket channel and is secure.

The other one is targeting the admin daemon and is of null interest if one is not concerned with the development of CVault (see the dedicated developers corner documentation).

If the number of returned values is -1, then the atomic transaction returns all of its value in a batch as shown for two queries we already met previously:

$ cvtools -S LS

cache: LS_MGRS; 4; < 0 = -1 >; no forward; shared; ux;

cache: LS_CACHE; 9; < 1 = -1 >; no forward; shared; ux; secure

$

To know all atomic transactions supported by the system, just give cvtools -S .*. The following go through all queries supported by the cache manager.

RET_CRED. We already know this one. The arguments are requester,user name,resource name and optionally the environment.TRASH_CACHE. We already met this one. Note that in case the DB is on file, then this query performs a clean reload of the dbfile.GET_USRKEY. We already met this one.MKEY_REMOP. We already met this one.EXPORT_DB. Triggers the cache manager to export the whole DB on a flat file. This query is secure and enabled only for registered clients which have MK privileges. The format of the generated file will be same the format of the file to import, described previously in this document. This is for management purpose only, since the cache manager is able to export the DB by itself if configured so. This feature is useful if one want cvcm to switch automatically to file DB in case of backend failure.LS_MGRS. We already met this one.RELOAD_CFG. This query is secure and enabled only for local registered clients which have MK privileges (for obvious DoS reasons). It allows to synchronously (with ongoing transactions) change the configuration of the cache manager. Should anything go wrong, then cvcm would exit. It is obviously an exclusive query.DUMP_CONFIG. Legacy. This secure transaction on Unix sockets only accepts the name of a configuration item in argument and return its value currently activated (may thus not always reflect the content of the configuration file). It was used by the client to get some configuration items synchronized with the running cache manager.DEREGISTER. This secure query available only locally instructs the cache manager to deregister itself from the DB. That way, it will never receive cascaded transactions from other cache managers of the CI. This may be useful to isolate an instance for maintenance or troubleshooting purposes.DB_HANGUP. This secure transaction (on both UDP and UX channels) instructs the cache manager not to touch the DB any more. It can only rely on its cache content to deserve transactions. If its cache is empty when receiving this query, then the cache manager logically shuts down.JOIN_NOTICE. On UDP channel only, this notice is sent to all cache manager by a new one which has just started up. Should one cache manager have a hangup status, it will then send this back to the originating cvcm, which then could lead to immediate shutdown.DB_RELEASE. The opposite ofDB_HANGUP.HANGUPSTATUS. Returns the DB access status of the cvcm, ob both UDP and UX channels.LS_CACHE. This secure transaction list one of the cache lines given in argument (“key, “cred” or “acl”). It is secure, accessible only locally and is always part of a serialized transaction.AUTOCALIBRATE. This exclusive secure query available only locally instructs the cache manager to find by itself the best threshold values determining the switch between linear cache and BTree cache (for ACL and credentials cache lines).SHUTDOWN. This query performs a graceful shutdown of the cache manager.GET_BINKEY. This secure query available only locally returns the key of the given client binary. This key, stored internally within cache manager and not in the DB, is returned encrypted with the Master Key. This transaction is only used by cvad when connecting with a binary which owns the MK privileges.SEC_INIT. This is the query for initiating a secured transaction. It takes the name of a (normally registered) binary and the ID of the atomic transaction to perform. The returned values are a transaction ID and a challenge.SEC_XEQ. This secure transaction is the second step: as arguments, it takes the transaction ID previously returned by cvcm and the answer to the corresponding challenge. The other arguments are the (encrypted) arguments of the secure query to run. The (encrypted) returned values are the responses to the query. This 2-step secure transaction implementation allows to run them on non-connected protocol such as UDP. Obviously cvcm will wait for a very short time between the SEC_INIT transaction and the followingSEC_XEQone. On high latency UDP wires, this may lead to transaction failures.SECMEM_ON. This secure transaction available locally switches cvcm in debug mode for the secure memory allocations, deallocations and mappings. Obviously cvcm must be launched in foreground from a terminal since the debug infos are printed on stderr.SECMEM_OFF. This secure transaction available locally switches secure memory debugging back off.

The last two transactions SECMEM_ON and SECMEM_OFF are only reserved for maintenance and debugging and are even available only via cvtools. The whole Credential Infrastructure must have been built with the flag _CVSM_DEBUG, which happens by running the configure script with the switch --enable-cvsmdebug. Due to obvious performances concern, this should never be used for production infrastructures.

Regarding the queries supported by the Admin daemon, the reader may refer to the Developer Documentation since there is very little maintenance to perform here.