CVault Internals¶

This guide will provide a deep dive into the Credentials Infrastructure internals. A previous reading of the User Guide is needed to catch the concepts exposed in this document.

Overall Description¶

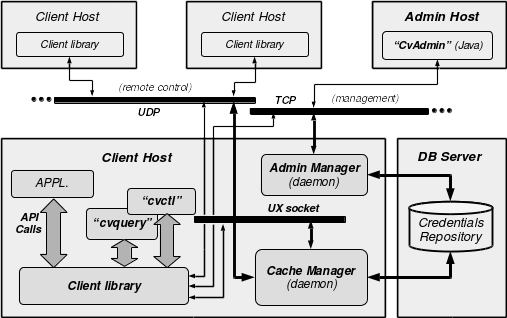

The figure below remembers the overall architecture. It has been described in the introduction manual and will be kept as red line for the description of the internal organization of the CI.

The most important to remember here is that the central component is the Cache Manager daemon (cvcm binary). It is reachable through 2 buses: a Unix socket bus for communications coming from local clients, and a UDP bus for operations performed for remote clients.

The second major element is the Admin daemon (cvad). Its main business is to act as a secure gateway to the CI data for either CLI management tool (cvctl) or a GUI management tool (cvadmin, written in Java).

A third component is the Core Library, which features an API to interact with the overall CI daemons either locally, or remotely.

We will start with the description of the data format exchanged, before we describe each low-level modules and libraries and then explain how they are articulated together.

Secure Memory¶

For the Credential Infrastructure we have introduced the notion of Secure Memory accessible for all components (daemons and command line utilities). In short, we have developed a dedicated memory manager - the library cvsm - taking care of memory allocation, de-allocation and protection.

Concepts¶

The main features are the following:

- memory held in core and not swappable,

- memory area underflow and overflow protection,

- xalloc, free and strdup primitives,

- an additional protect primitive,

- debugging facility if compiled accordingly.

The data structure held in the caller’s memory space (which the caller is not supposed to touch) is the following:

typedef struct cvsm_s {

pid_t pid; // of the caller process

void *secmem; // overall area locked into core

size_t areasz; // aligned on pages size

void *mapbeg; // start of the secure memory

void *mapend; // End of the secure memory

uint32_t mapsz; // Size of the usable memory area

pthread_rwlock_t *prwlck; // in-process RW lock

} cvsm_t;

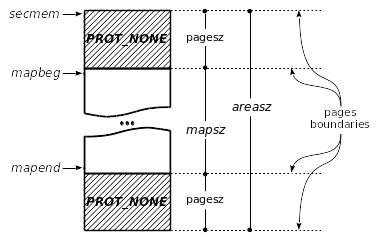

The figure below shows the map of the secure memory right after initialization and gives the explanations of each member of the structure cvsm_t:

The areasz is the amount of memory claimed by the caller during the initialization. This size is aligned on the page size boundaries and 2 pages are reserved to provide barriers at the upper and lower bounds of the usable memory. Should a badly controlled memory operation reach one of those forbidden pages, then the whole process will terminate immediately with a memory access fault (and very likely with a SIGSEV or SIGBUS as well). Those two pages are taken from the overall reserved memory of the caller, which means the amount really available is two pages less than reserved. We made the decision not to claim two extra-pages for configuration consistency. Indeed, reserving this memory demands some privileges which have to be configured in the system, and it is consistent to configure such privileges for the amount of memory the process will effectively reserve.

This data protection has a counterpart regarding the performance and memory consumption overheads it brings. But in security concerns, there are no trade-off, so we want to accept the costs of this security enhancements.

Implementation¶

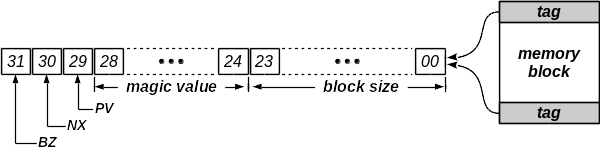

The memory is managed as blocks of 2 kinds: either allocated blocks or free blocks. Each block holds its management data within itself as tags placed at the very first address and at the very last address. In the rest of this document, we will further refer to them respectively as heading tag and trailing tag.

The picture below describes such a memory block and highlights the management tag. A tag is 32 bit wide and a memory block is at minimum 256 bytes big, making the minimum allocatable space to 248 bytes.

The first 24 bit of the tag contain the size of the block (making the max size of a block to 16 MB). The next 5 bits define a magic value, encertaining that the block is valid. This magic number is dynamic and randomly determined at the initialization of the secure memory and is constant during the entire life duration of the secure memory (i.e. until the next call to finalize() or program exit). The last 3 bit are management flags with the following meanings:

- PV: the previous block is valid. The management tag of the previous block is therefore accessible at the address of the heading tag of the current block minus the offset of the tag size. The first block has PV set to zero, since the previous block is a forbidden page.

- NX: the next block is valid. The management tag of the next block is therefore accessible at the address of the trailing tag of the current block plus the offset of the tag size. The last block has NX set to zero, since the next block is a forbidden page.

- BZ: the current block is busy or allocated.

Both heading and trailing tags of a block must obviously have the same value, and this helps to enforce the validation or corruption checks of a memory block. Moreover, this double block tagging allows to access directly from one block to the adjacent ones and a navigation across all blocks in both directions is therefore possible without having to manage any sided data structures such as linked list or the like.

Memory Allocation¶

A memory allocation occurs by a call to xalloc() and consists of the following steps (Knuth “TAOCP Vol.1, 2nd edition”, chapter 2.5: “Best Fit Algorithm”):

- Scan the memory blocks to find the smallest free block which fits the size requirements.

- Select the best free block and extract an allocated block from it.

- Shrink the free block to the remaining size. Note that if the remaining size of the free block is not big enough to be allocated later (size less than

CVSECMM_CHUNK_SZ) then it will never be selected during future scan. To avoid letting an unusable free block, it is merged into the freshly allocated block (we favor internal fragmentation).

All this occurs atomically under the acquisition of the lock prwlck.

We also tried the Best Next Fit Algorithm, but experimentation showed that in our case, it had a very negative impact on the external fragmentation. The performances of our memory scanning are highly sensitive to the number of blocks to walk through and we decided therefore to drop the “Best Next Fit Algorithm”. On the other hand, we enforced the memory coalescence at de-allocation to guarantee that there will never be two consecutive blocks of free memory. This brings our “Best Fit Algorithm” to behave almost all the time as the “First Fit Algorithm”.

Memory liberation¶

Memory liberation occurs by a call to xfree(). It is a slow process since it also endorses the maintenance of the memory area. The de-allocation occurs in the three following steps:

- The address to free is thoroughly checked and once the block it belongs to has been identified, the block is checked for data corruption. Should the address or the block be invalid, the call is considered faulty, and the program is terminated immediately by calling the macro

CVSM_SIGSEVME(). This macro generates a memory fault and if the program has not been killed, it callsabort()afterward. This behavior is arguable: one could just mark the block as unusable and continue. The rationale behind this, is that if an illegal access occurred, then something is wrong in the caller’s code. If it is a bug, the developer will very likely fix it asap. If it is an attack of an exploit which worked successfully, then it is not that bad to kill the caller the earliest: the developer will have to fix the weakness asap as well. - The block is marked as freed and the tags are updated.

- Free blocks are coalesced. The adjacent upper and lower blocks are checked as well. Should one of these blocks be also a free block, then it is merged with the freshly freed current block.

Memory protection¶

Till here, we talked about two kinds of blocks: allocated or free. In fact, there is a third kind of block: the forbidden block or hole block. This block is always aligned on page boundaries and is always the size of an entire page. This size is system dependent. The role of a forbidden block is simply to prevent memory access to occur within the address space belonging to the block. Should a former allocated block witnesses a buffer overrun, or a next allocated block suffer from buffer underrun, then the access will finally reach this forbidden area. What happens then is also system dependent. On Solaris, Linux, AIX, Mac OS, FreeBSD and OpenBSD the process performing this faulty memory access is terminated immediately, or killed, which is what we want.

Memory protection occurs by a call to protect(). The block to protect is the one which owns the address given in argument, address returned by a previous call to xalloc(). We consider memory protection as not structuring but rather a “nice-to-have” feature. Indeed, the most important is that the previous call to xalloc() succeeded and that the caller may work with the freshly allocated memory. Therefore, no failure from protect() are lethal for the calling process.

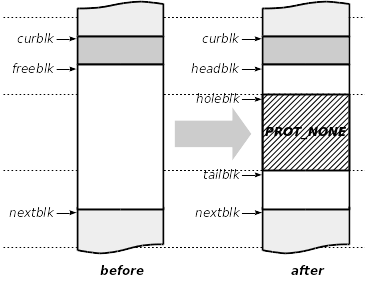

The following picture explains how the protection works. The pointer curblk points to the area to protect. The free block right after is designated by freeblk. The dashed lines represent the page boundaries of the memory map. The protection process follows the two steps:

- Identifies within the next free block the next page boundary. If the next block is already a forbidden one, then

protect()fails. If this free block doesn’t contain a full memory page, thenprotect()fails. If the remaining free space would be too small to build a new free block, thenprotect()fails as well. Otherwise, we mark the page within the free area - pointed to by holeblk - as forbidden by issuing the ad hocmprotect()syscall. - The free area is then split into two free blocks and we face here two possibilities. The figure below shows the case where the new free heading block is big enough: in this case the memory manager creates two new free blocks: one before the hole block, one after the hole block and we are done.

The picture below shows the case where the heading space will be too small to build a new free block. In that case, the memory manager merges this area with the previous allocated block, which is the block to protect. However, the caller is still not supposed to touch this area and we don’t want to provide a kind of buffer overflow protection by appending a zero-filled memory area. For this reason, this shadow block is filled with the arbitrary value 0xed. Should a buffer overrun occur within the protected block, then it will traverse the shadow area as well to finally reach the forbidden block.

The success of this operation is never guaranteed, even by calling protect() right after xalloc(). However, the caller get noticed of the success or failure and may in the later case free the area to protect and claim an allocated area with intrinsic protection at once by calling xalloc_prot().

xalloc_prot() performs basically a big enough memory reservation followed by a split of the remaining area into a hole and a new free block. Since these operations are performed within the same critical section with the right sizing, the likelihood of success is very high. The counterpart is that it is very slow. Note that the parameter used for the Best Fit algorithm here is the smallest allocated size, regardless of the size of the remaining free area.

A block adjacent to a hole at lower bound will have its tag flag NX set to zero (resp. PV set to zero if hole at upper bound). Since the holes are forbidden memory area even for the memory manager, there is no tag to read. The hole detection during memory scanning is intrinsic:

- blocks claiming to be the first with PV set to zero although their address is bigger than the first one (mapbeg) are preceded by a hole.

- blocks claiming to be the last with NX set to zero although their address is lower than the last one (mapend) are followed by a hole.

The liberation process detects the holes and performs a merge between a freshly freed block with the next hole if necessary. The same way, the allocation process detects holes and jump to the next block when scanning memory for a good free block candidate.

Debugging facility¶

If the library is compiled with the compiler flag -D_CVSM_DEBUG (or configured with --enable-cvsmdebug) then the structure cvsm_t is augmented with the following entries:

typedef struct cvsm_s {

...

int debug; // debug mode is activated

unsigned xalloc; // counter of xalloc ops

unsigned xfree; // counter of xfree ops

unsigned allocblks; // counter of allocated blocks

unsigned freeblks; // counter of freed blocks

unsigned holeblks; // counter of forbidden blocks

} cvsm_t;

and three additional functions are available: cvsm_debug_start() and cvsm_debug_stop() respectively enters and quits the debug mode and cvsm_debug_reset() resets the statistic counters to zero.

For deeper details on the debugging functions of the API, please refer to the corresponding manpages cvsm_debug(3).

When activated, the debug mode dumps a high-level description of each block with the following fields:

- address of the block

- head and tail tag values (should be the same)

- SZ: size in bytes

- MV: magic value

- PV flag interpreted

- NX flag interpreted

- Status “OK” for valid block or ”!!!” for corrupted block.

The following gives an example of the first allocated block of 1280 bytes:

blk: 0x00007fe93ab52000 [0xc5000500][0xc5000500] - SZ: 1280 - MV: 0x05000000 - A - FIRST - NEXT - OK

The hole blocks are represented with “#” in the field values, since there is no memory accessible. The are reported like the following:

blk: 0x00007fe93ab53000 ######################## - SZ: 4096 - ################################# - OK

As example, the following small program highlights the differences between the calls to xalloc() + protect() and xalloc_prot():

#include <cvsm.h>

CVSM_USE_SECURE_MEMORY;

int

main( int argc, char **argv ) {

int rc;

void *p;

rc = cvsm_initialize(64, NULL);

if ( rc < 0 ) {

fprintf(stderr, "*** No secure Memory.\n");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

cvsm_debug_start(0, 0);

p = cvsm_xalloc(1234);

cvsm_protect(p);

cvsm_xfree(p);

p = cvsm_xalloc_prot(1234);

cvsm_xfree(p);

cvsm_finalize(1);

return 0;

}

The call to cvsm_protect() will generate the output given below. On can particularly notice that the free block before the hole is denoted as the last block and the free block after the hole is marked as the first block (and the last as well, but it is really the last one in that case):

...

= PROTECT(0x7f368c3b7004): insert hole @ 0x7f368c3b8000

= blk: 0x00007f368c3b7000 [0xc9000500][0xc9000500] - SZ: 1280 - MV: 0x09000000 - A - FIRST - NEXT - OK

= -----------

= SEC MEM MAP

pid: 21557

beg: 0x7f368c3b7000 - end: 0x7f368c3c4fff - size: 57344

xalloc: 1 - xfree: 0

= blk: 0x00007f368c3b6000 ######################## - SZ: 4096 - ################################# - OK

= --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

= blk: 0x00007f368c3b7000 [0xc9000500][0xc9000500] - SZ: 1280 - MV: 0x09000000 - A - FIRST - NEXT - OK

= blk: 0x00007f368c3b7500 [0x29000b00][0x29000b00] - SZ: 2816 - MV: 0x09000000 - F - PREV - LAST - OK

= blk: 0x00007f368c3b8000 ######################## - SZ: 4096 - ################################# - OK

= blk: 0x00007f368c3b9000 [0x0900c000][0x0900c000] - SZ: 49152 - MV: 0x09000000 - F - FIRST - LAST - OK

= --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

= blk: 0x00007f368c3c5000 ######################## - SZ: 4096 - ################################# - OK

= SEC MEM MAP : alloc blocks: 1 - free blks: 2 - hole blks: 3

...

The following output shows the memory structure after the call to xalloc_prot(). One can see the main differences of behaviors between both ways of protecting memory: in the previous example, the remaining area is made available as free block and in the second example, the remaining area is merged within the allocated block (filled with non-zero value):

...

= 2:XALLOC_PROT(1234)

= best:0x7f368c3b7000: 4096

= 3:xalloc(5338) = 0x7f368c3b7004

= blk: 0x00007f368c3b7000 [0x89001000][0x89001000] - SZ: 4096 - MV: 0x09000000 - A - FIRST - LAST - OK

= -----------

= SEC MEM MAP

pid: 21557

beg: 0x7f368c3b7000 - end: 0x7f368c3c4fff - size: 57344

xalloc: 3 - xfree: 1

= blk: 0x00007f368c3b6000 ######################## - SZ: 4096 - ################################# - OK

= --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

= blk: 0x00007f368c3b7000 [0x89001000][0x89001000] - SZ: 4096 - MV: 0x09000000 - A - FIRST - LAST - OK

= blk: 0x00007f368c3b8000 ######################## - SZ: 4096 - ################################# - OK

= blk: 0x00007f368c3b9000 [0x0900c000][0x0900c000] - SZ: 49152 - MV: 0x09000000 - F - FIRST - LAST - OK

= --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

= blk: 0x00007f368c3c5000 ######################## - SZ: 4096 - ################################# - OK

= SEC MEM MAP : alloc blocks: 1 - free blks: 1 - hole blks: 3

...

It is clear that using the debugging functions considerably slows down the calling process.

API of the library ``cvsm``¶

We didn’t want to hide anything in the API of this library. Using a single header for the interface and the implementation, we made everything visible. Obviously, the caller remains not supposed to deal directly with the data structure that cvsm injects within the caller’s memory space for its own purposes.

A program, which needs the secure memory wants to declare the following in its global name space:

CVSM_USE_SECURE_MEMORY;

The library cvsm attaches then the caller’s secure memory as external object, resolved at linked time.

This is the simplest way to get a fully re-entrant interface while still opaquing the dedicated data structures needed by the library. The interface sticks to the standard syscalls malloc() and free(). The API consists then in the following 7 functions:

cvsm_initialize(): set-up a virtual memory area within the caller space.cvsm_finalize(): clear and free the secure memory area of the caller.cvsm_xalloc(): reproduces the standard syscallmalloc().cvsm_xfree(): reproduces the standard syscallfree().cvsm_strdup(): reproduces the standard syscallstrdup(), provided for convenience.cvsm_protect(): sets an overrun protection close to the targeted secure memory block.cvsm_xalloc_prot(): allocates and sets over-run protection right after the reserved memory block.cvsm_strerror(): convenience function to parse error codes like the syscallstr_error().

For deeper details on the functions of the API, please refer to the corresponding manpages cvsm(3).

It is wise to know that the atomic allocation is 256 bit. It would help to reduce performances overhead by considering merging several smaller chunks into a structure closed to this value instead of performing individual allocations. As side effect, the memory waste would get better as well.

CV Data Structures¶

The main design decisions, which have been made at the soonest and decided afterwards the implementation of almost all other features.

Atomic Transaction Representations¶

In the Administration & Maintenance Guide, we introduced the concept of atomic transaction. We will present here the details of the different representations and the API functions related to their handling.

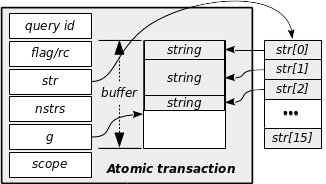

As shown in the picture, a transaction has three main parts, which are transmitted between entities:

- A query id. It tells the peer what action we want it to perform (and tells back to the sender what action has been proceeded).

- A flag giving indication on the transaction. In the response it contains the return code (standard 0 in case of success, negative in case of failure, positive if there is a particular message).

- A buffer of strings. These strings give the arguments necessary to perform the action. At return they give the responses after completion of the action. The buffer of an atomic transaction can currently store up to 16 strings, with a total size limit of somewhat 4000+ bytes: this size is currently sufficient to transmit a whole X509 certificate.

- nstrs defines the number of strings currently stored within the buffer. A NULL terminated array is not always suited for quick data access.

Additional sided entries have been defined as helpers, which are not transmitted:

- scope is used for internal logging. It defines the log level with should be used for this atomic transaction.

- str points to an array allowing fast access to individual string within the buffer. This table is not stored within the atomic transaction address, but outside since it is never transmitted.

- g points to the first free address within the buffer, where to store the next string. It makes obviously no sense to transmit it since the sender and receiver are two different processes with two different addressing spaces.

The corresponding definition of this fundamental data structure is the following:

typedef struct cv_atx_s {

unsigned char qid;

unsigned char nstr;

char flagrc;

unsigned char scope;

char *g;

char **str;

char buff[CV_QBUFLEN];

} cvatx_t;

As explained in the Administration & Maintenance Guide before, just the informative data are exchanged. This leads to the following second data structure which really transmitted over UX sockets:

typedef struct cv_atxw_s {

unsigned char qid;

unsigned char nstr;

char flagrc;

char buff[CV_QBUFLEN];

} cvatxw_t;

The value of CV_QBUFLEN is defined in order to guaranty that the size of the transmitted structure cvatxw_t is always 4096 bytes as explained previously. Its definition is:

#define CV_QBUFLEN 4096 - ( 2 * sizeof(unsigned char) + sizeof(short) )

This simplified structure raises then the problem of rebuilding the full structure at reception, particularly the pointers to the strings in the array str and the value of the gauge g. We will see later how this problem is solved.

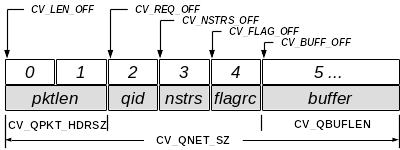

The third representation addresses the way this transaction is transmitted over the wire. Here we have an additional problem to solve: since the data are exchanged across a network, we can’t guaranty that both sender and receiver have internally the same byte ordering for integer representations. We must address this point.

We will simply transmit a packet of bytes of variable size: only the current content of the buffer get transmit instead of the whole bunch of CV_QBUFLEN bytes. For the receiver to collect the right amount of data, we send the overall packet size as header. We used the little-endian representation for 2-bytes integers because it is the mostly used. The endianness is detected at compilation time and the conversion functions are then replaced on most architectures as standard casting.

Since we transmit only one integer bigger that one byte, we don’t mind offending the standard network byte ordering, which is big-endian. The packet content looks like in the following picture:

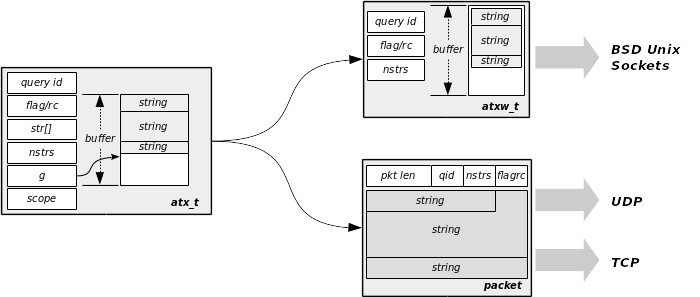

The CVault Core Library libcv provides helpers to translate one representation to the other. These helpers are internal since the client at high level doesn’t need to deal with these details. The table below summarizes the translation features available (source file cvapi_net.c):

| AT types | atx_t (native) | atxw_t | packet |

|---|---|---|---|

| atx_t | na | _cvnet_bin2net | cvint_net_atx_pack |

| atxw_t | _cvnet_net2bin | na | na |

| packet | cvint_net_atx_unpack | na | na |

The CVault Core Library provides a set of primitives useful to write a client dealing with the daemons. All client interface is summarized in the single header file cv.h. For internal needs, the library provides a dedicated interface described in the header cv_internal.h, where all exported functions are prefixed cvint_*().

The figure below summarizes the transformations of an atomic transaction to send in regard to the end protocol in use:

Description Tables¶

The CV Core Library maintains and exports two symbols cm_qinfo[] and ad_qinfo[] giving a general description of each atomic transaction supported by cvcm and cvad respectively. These symbols simplifies the syntax check for the client or servers when dealing with an incoming transaction.

The structure of the elements of these tables are described in cv.h. For cvcm supported queries, the structure is the following:

typedef struct cvcm_atxinfo_s {

void (*callbk)(cvtxn_t *); /* callback running this query: internal use only */

int loc; /* Enabled locally as non admin */

int rem; /* Enabled remotely as admin */

int pargs; /* nb of parameter arguments of the query */

int rvals; /* number of awaited answers (-1 means batch query) */

int sec; /* Query to run within secure session */

int bcast; /* Request is broadcastable (cascadable) */

int excl; /* Query exclusiv: thread access WR to common resources */

const char *qname; /* Name of the query */

} cvcm_atxinfo_t;

CV Core Library initializes this table with the macro CVCM_ATXINFO_TBL defined in cv_internal.h. For example, we have the following definition for the query RET_CRED:

cm_qinfo[C_RET_CRED] = { NULL, CV_EN, CV_DIS, 4, 1, CV_SEC, CV_ONE, CV_NEX, "RET_CRED" }

This structure may be used by anyone. As example, checking whether a transaction is supposed to be secure or not is reduced to the check of the value of the flag cm_qinfo[qid].sec.

For cvad supported queries, the structure is the following:

typedef struct cvad_atxinfo_s {

void (*callbk)(cvtxn_t *); /* callback running this query: internal use only */

int pargs; /* Number of arguments */

int rvals; /* Number of answer(s) */

int dbmod; /* Query modifies DB */

int sesst; /* session type main or edge */

#define EDGE_S 0x04

#define MAIN_S 0x08

const char *qname; /* Name of the query */

} cvad_atxinfo_t;

This structure may also be used by anyone. As example, checking whether a cvad transaction is supposed to occur within the main session or the edge session is performed by the check of the value of the flag ad_qinfo[qid].sesst.

The first argument of both structures callbk is initialized at the startup of the daemons. They contain the address of the callback which will process the incoming atomic transaction. There are supposed to be only one instance of each daemon running actually. A “double load” will result in unpredictable behavior, mainly with a sorry end. On the other hand, these tables are updated only when the daemon enters effectively into the listening main loop. This allows a parallel run as command line utility - registration of new binary, generation of new keys, etc. - since in that mode, the programs will never enter into any listening loop.

API functions¶

The following functions from the CV Core Library are available to manipulate the atomic transactions.

cv_atx_new(): allocates and initializes a new atomic transaction in secure memory.cv_atx_clone(): create a verbatim copy of the atomic transaction given in argument.cv_atx_clear(): empties the content (arguments and returned values) of the given atomic transaction.cv_atx_reset(): reinitializes the given atomic transaction for reuse.cv_atx_destroy(): erases and releases the memory allocated by the given atomic transaction.cv_atx_calloc(): performs an in-buffer area reservation, within the given atomic transaction.cv_atx_strdup(): copies within the buffer of the atomic transaction the string given as argument.cv_atx_freestr(): releases and clears the string area within the buffer of the atomic transaction.cv_atx_dump(): dumps the content of the atomic transaction in stderr for debugging purposes.

For deeper details upon these functions, please refer to the corresponding manpage cv_atx(3).

Protocols¶

As highlighted in the Admin & Maintenance Guide, there are three types of transmission protocols:

- The sessionless transaction: a client sends an atomic transaction, waits for the response (or times out) and closes the connection.

- The secure transaction: only accessible to the client binaries registered (with the command

cvcm -s) or to clients using remotely a pre-registered Client Unique ID with its key. It is a two-steps protocol, where the client has to authenticate itself first before sending an atomic transaction and receiving the responses, all encrypted with the authentication key. - The batch transaction: the return data set of a query are serialized across a set of several atomic transactions. The transaction initializing a batch return may be either a simple or secure transaction.

We are supporting three types of communication channels with the daemons: Unix BSD sockets, UDP or TCP wired connections. The support matrix is summarized below:

| Txn vs Channel | UX | UDP (cvcm only) | TCP (cvad only) |

|---|---|---|---|

| sessionless | X | X | na |

| secure txn | X | X | X |

| serialized txn | X | na | X |

We described the protocols in the Admin & Maintenance Guide at high level: we will concentrate here on the details of the internal processing.

Sessionless transactions with the cache manager¶

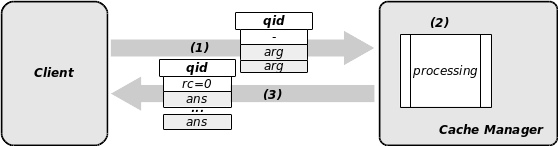

The following picture highlights the processing during the transmission. In fact, cvcm performs just some standard controls against the requester and processes the transaction as is. The returned values are placed within the buffer and sent back to the sender. This type of exchange concerns only simple commands and non privileged atomic transactions:

Note that only the cache manager cvcm supports this protocol. The general processing of the transaction occurs within the module cvcm_rpc and the individual execution of each atomic transaction occurs within the module cvcm_callback. We will discuss later about the internal organization of the daemon binaries.

If the channel used is UDP, then the client is not supposed to wait for an answer: the atomic transactions transmitted using this channel are only commands cascaded from a cache manager to its peers. Therefore, the step (3) doesn’t exist in that case. Moreover, being an internal feature (only the daemons may send a query on UDP), there is no published primitive for the external clients in the CV Core Library API.

The published function of the API dealing with this simple protocol over BSD Unix sockets is cv_net_ux_sendrecv(). Please refer to the manpage cv_net(3) for details.

Secure transactions with the cache manager¶

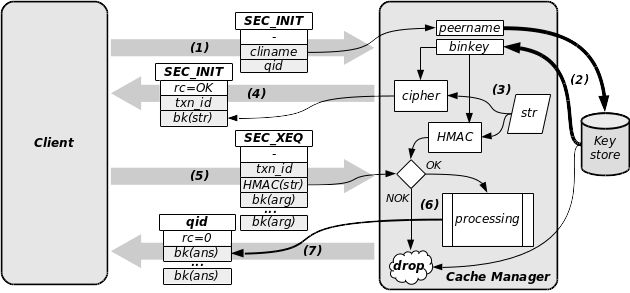

As illustrated in the picture below, there is a little bit more to do with such transactions. This protocol enforces the security level to the data exchange. All concerned atomic transactions have their security flag set (i.e.: cm_qinfo[qid].sec = 1). The overall flow is the following:

- the client binary send a

SEC_INITatomic transaction with its name and the query id it wishes cvcm to run. - cvcm performs a lookup in its keystore and retrieve the binary key corresponding to the client name. In case of lookup failure, the overall transaction is dropped here.

- cvcm starts to authenticate the client: it generates an arbitrary string, which get encrypted and HMAC’d with the corresponding binary key.

- The encrypted arbitrary string is then sent for challenge as the answer of the

SEC_INITtransaction. A transaction ID is also sent because we are not in a connected session here. - The client will have to decrypt the arbitrary string and compute the HMAC on the plain text. It sends this HMAC together with the transaction id it has received and with the encrypted arguments which have to be processed with the former query id. This builds the

SEC_XEQatomic transaction. - The cache manager compares the HMAC sent by the client to its pre-computed value. If they fit, the authentication has succeeded and the atomic transaction is processed. If they don’t fit, the overall transaction is dropped here.

- On success, the results are encrypted and sent back to the client as a standard atomic transaction answer, using the corresponding query id. The client must decrypt the answers before using them.

Here also a secure query running over the UDP channel is only for internal purposes and therefore the CV Core Library API exports no primitive to the external clients. For the BSD Unix socket channel, the primitive cv_net_secquery_run() is available. Please refer to the manpage cv_net(3) for details.

Serialized transactions¶

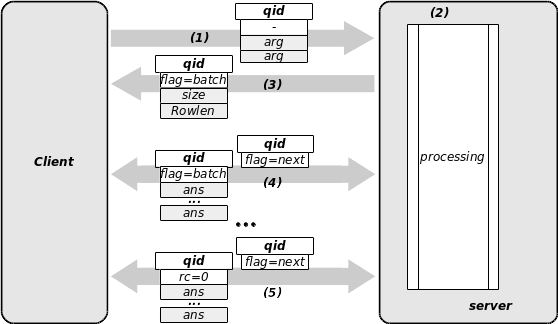

As illustrated in the picture below, there is even more to do with such transactions. All concerned atomic transactions have their return values amount member set to a negative value (i.e.: cm_qinfo[qid].rvals = -1). the serialized atomic transactions or batch queries protocol addresses the case where the return values of a query don’t fit within a single atomic transaction. In such cases the return values are serialized across a set of several atomic transactions, or - from another point of view - the atomic transactions are embedded within a batch. The overall flow is the following:

- The client sends a query with its arguments.

- The server processes the query and keep all result within memory.

- It answers with the flag announcing a batch: the returned values of this first answer give the size of the table being returned. This allows the client to perform beforehand any necessary memory reservation.

- The client enters then a loop: it asks for the next data with a flag requesting the next bunch of values. The server sends an atomic query with the flag announcing that the batch continues.

- The server closes the batch with the last atomic transaction having the flag set to 0 (success). The client closes the transactions.

There is no limit in the number of atomic transactions within a batch: the amount of data transferred in an answer may be of arbitrary size. The data returned is to be considered as a table of size rows and rowlen columns. The only constraint is that at least one full row must fit within an atomic transaction, limiting therefore the table to 16 columns for an overall amount limited to the buffer size.

When dealing with confidential data, the serialized atomic transactions may also be used within a secure transaction. In this case, the batch is opened after the client authentication and all data returned are then encrypted with the binary key of the client.

An external client is only concerned with the reception of a batch transaction. Therefore, the CV Core Library API exports only the related primitives cv_net_tcp_batchrx() and cv_net_ux_batchrx() for the TCP and BSD Unix socket protocols respectively. Please refer to the manpage cv_net(3) for details.

Dealing with those different protocols according to the atomic transaction to run may make an external client difficult to write. For this reason, the CV Core Library API exports a single primitive which wraps everything together, making the right choice of the protocol and channel to use in accordance with the atomic transaction definition: cv_util_cmclient_txn(). All external clients should use only this primitive to communicate with the cache manager. Please refer to the manpage cv_net(3) for details.

Session with the admin server¶

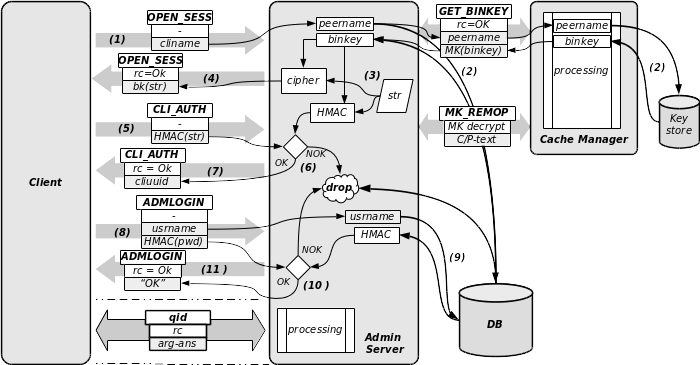

The administration server cvad uses the same data representation as the cache manager. The protocol uses the TCP channel only and there is only a single stateful session at a time - the main session - with possibly a short-live edge session. Setting up a session with the admin server follows the flow given in the picture below. It seems complex, but in fact it just reuses the concepts exposed previously (and in majority the same source code):

- The client sends an

OPEN_SESSatomic transaction, with the client name in argument. - If the client is a binary which have Master Key privileges, then cvad sends a secure

GET_BINKEYquery to the cache manager, which will send back the corresponding binary key retrieved from its key store. If it is a commonly shared cliuuid, then cvad retrieves the corresponding key from the DB. Since those keys are MK encrypted in the DB, cvad will send a secureMK_REMOPto cvcm to get this binary key decrypted: in both cases the cache manager is involved in the opening session. - With the binary key, cvad will prepare an authentication challenge the same way as cvcm performs the client authentication for secure queries.

- The challenge is sent as answer to the

OPEN_SESSatomic transaction. - The client will then decrypt and sends back the HMAC of the arbitrary string within a new

CLI_AUTHtransaction. - cvad performs the check and drop the connection in case of failure.

- cvad sends back the client name as acknowledgement of a successful client authentication.

- Then the client sends an

ADMLOGINatomic transaction with a username and the HMAC of the user’s password. The key used for this HMAC encoding is the binary key of the client. - cvad performs a control of this HMAC with the value stored in the DB. Any failure drops the connection.

- In case of success, cvad just sends an “OK” back as answer to the

ADMLOGINatomic transaction.

From now on, the client and the admin server may exchange any transaction (dashed lines) until a timeout occurs (client idle timeout) or the client sends explicitly an ADMLOGOUT transaction. All communications are encrypted using the binary key of the peer or the key used by the shared cliuuid previously authenticated. The transactions used during the main session can be either atomic transactions or serialized transactions.

The CV Core Library exports the following primitives to clients communicating with the admin server:

cv_net_adsess_open()performs the client authentication with cvad.cv_net_aduser_authperforms the administrator login to cvad.cv_net_ip_sendtosends an atomic transaction over the opened IP wired without awaiting an answer (may also be used for UDP socket).cv_net_tcp_sendrecvsends an atomic transaction and waits for the answer.cv_net_tcp_batchrxmanages the loop receiving all data from a batch.

Please refer to the manpage cv_net(3) for details.

In this section, we presented the most important primitives of the published API of the CV Core Library. One great client to study as illustration on how to use this API is cvtools. On the other hand, the best example with a clear separation of cvad client code and cvcm client code is given by the utility cvctl.

Server daemons internals¶

In this section will dive into the internal organization of the servers, with particular higlights on the previous “processing” units given in the illustrations. Having the sources tree imported into an IDE (we use Netbeans) would be helpful to follow the code. We will use cvcm as example, which is the most complex server. On the other hand, cvad is the “biggest” in term of atomic transactions it has to deserve to its clients.