Introduction¶

Conceptual features¶

The “Credentials Vault” (CV) sets an overall software infrastructure in the data center with the purpose, in short, to introduce a kind of CLI utility with the following format:

retrieve_cred <username> <resourcename> [container]

to get an answer in a secured manner, obviously provided that the requester is indeed allowed to do so. It becomes then possible for any application to get the credential(s) it needs to access any protected resource, and this without the need of saving these passwords in some sort of local configuration files of the application.

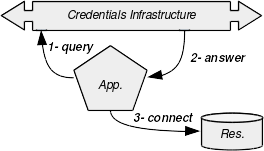

The figure bellow summarizes the dynamics of the operations:

In this example, the application needs to connect to an external resource such as a database using a username and a password. At the startup, the application will send a retrieval query to the Credentials Infrastructure (further noted “CI”) : the operation noted 1 in the figure. After some verifications against the requester, the CI returns the password (step 2). Then, the back-end of the application can decrypt this password and connect to the database, using the provided credentials (step 3). The binding capabilities of the applications to the CI are provided by a dynamic library for native applications. Other technologies (Java/J2EE, C#/.NET, Ruby/Rail, etc) may be supported in the future.

Structure of a typical deployment¶

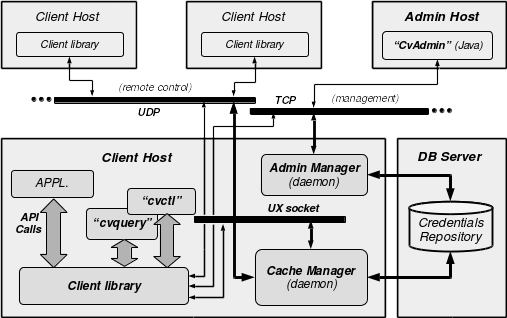

Basically, the architecture relies upon a standard distributed three tiers infrastructure, as depicted at the figure below. The heart of the system is the Cache Manager daemon and a client library running on the same host. Communications with the CI occur all through API calls to the client library.

The client library communicates with the Cache Manager locally using Unix sockets (PF_INET family). The library can also talk to a remote Cache Manager for special remote control purposes. In this case, the channel used is UDP sockets. The Cache Manager exchanges data with the DB back-end using standard TCP connections. On top of the client library, an application interfaces with the CI via API calls.

The CI provides two standard command line interface utilities:

- cvquery allows to retrieve credentials from the DB, the main purpose of the CI,

- cvctl is used to basically manage some CI features from a terminal.

Both stand for a good application example using the API. It is the Cache Manager which decides whether to fulfill the query sent by the client library or not. This decision is based upon access control data, the client host qualification (administrative host or simple client), and obviously the binary key used by the client.

The infrastructure contains a second daemon dedicated to the management. The Admin Manager daemon acts as a client for the Cache Manager using Unix sockets. It also acts as a server for a Java based GUI application “CvAdmin” and the CLI Unix utility “cvctl”, both TCP connected.

The credentials managed by the CI get decrypted only at the client library level, and within a dedicated secured memory space of the calling application. Moreover, in order to avoid any use of the client library to perform brute force attack against the passwords, it is by design not feasible to use the cryptographic capabilities more than ten times per second...

For maintenance, tests and audit purpose, the CI provides a third utility “cvtools”. Written in poor C, this quick and dirty tool is not intended to be deployed, but only to be used on some specific qualification hosts: indeed, it allows any kind of weird things such as stilling identity of any other client, sending uncontrolled hand-crafted queries to anyone, and the like.

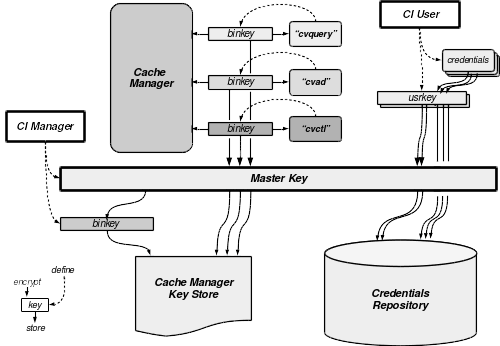

Cryptographic considerations¶

The overall cryptography relies upon a Master Key, which is given by the manager of the infrastructure. Each binary operates its own symmetric key for its cryptographic needs. This key is unknown from anyone, but PBKDFv2-derived from the binary structure itself combined with local properties of the running host. This means that the key of each program is subject to change at each new binary generation and deployment. It also means that the same version of a given binary will have different keys on different hosts. This is - almost - not a problem per see, since none of the utilities have to store or share any encrypted data.

This is not the case, however, for the Cache Manager which stores the Master Key in a file, using its own binary key. The binary key of the Cache Manager is PBKDFv2-derived only from a password given at startup by the CI manager (and also combined with local properties of the running host). At each new binary generation, the manager doesn’t need therefore to regenerate the Master Key file. The reason why the Cache Manager needs a passphrase is given by the obvious needs of confidentiality of the Master Key. Indeed, it is always possible for root - for example - to use the binary key of a program, since they are self-generated. For the Master Key, however, even root can’t decrypt it so long she has no clue of the binary key the Cache Manager uses to store it into the Master Key File.

The Cache Manager uses the Master Key to encrypt and store the binary keys of each client supposed to communicate with it. Each client can get the Cache Manager running “secure queries” on their behalf. However, this will only happen if the Cache Manager can ensure that the client is the one it states: this client ID verification occurs through its binary key verification (more on this later). Then, this binary key will be used to encrypt all exchanges between the Cache Manager and the verified client. We don’t need any PKI here, since the very low amount of possible clients makes the central management of private symmetric keys a viable solution.

Credentials that the CI manages are stored encrypted in the DB using a so-called “user key”. This means that the key used to encrypt each of them is selected by the end-user. These keys are not managed by the CI at all: the end-user retrieving an encrypted credential via the CI must also ask for the right user key. The client will use it to decrypt the returned credential. These user keys are stored in the DB encrypted with the Master Key.

Note that only the Cache Manager performs cryptographic operations with the Master Key.

The symmetric cipher used is “Twofish”, 128 bit clock cipher, with key length of 256 bit. It is one of the five finalists of the AES contest (hence the robustness), and is free of any patents for implementation (see http://www.schneier.com/twofish.html for details). We use it as CFB mode cipher, and as PRNG as well.

Features¶

In this chapter, we will review all features currently implemented in the CI, and propose some directions of possible enhancements. Currently, the status is “production”, which means the system works. It aims to have been tested, but as usual, slyly bugs certainly remain somewhere. The distribution have been “GNU autotoolized” and it builds successfully on Solaris (both Sparc and x86), AIX, Linux, *BSD and Mac OS X. A Windows/Cygwin port is on its way...

Data semantic¶

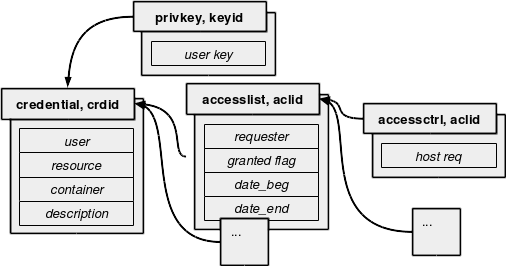

The data consist mainly of credentials, their encrypting user key, access lists and access controls. The following figure shows the organization.

The main data object is obviously the credential itself. It is controlled by an access list object, which itself is controlled by an access control object. Note that there is no control from the user key object: this means that the data stored in the DB give no relation between an encryption key and a credential: it is a knowledge that the end user must bring to the CI (however, a default key id may be defined in the configuration of the cache manager - defaulting to the keyid 0).

The access list object gives the login name of the requester who is supposed to access the credential. The validity duration is defined between the date when the access were granted and the date when access will be removed. An additional flag allows to quickly toggle the access (it is not an overriding flag: it must be true for the access to be granted). The access control object defines the host names where the requester is allowed to perform the access from. The control against the hostname is performed by reverse-lookup of the IP address of the server the cache manager is running on. Therefore, a user must perform his request from the right host and within the right time frame in order to access to a given credential.

Cache Manager¶

The cache manager, cvcm, is the heart of the system. It can run either as a standard program or as a daemon, depending the features the caller wants to use. When not running as daemon, cvcm can be used to generate an encrypted MasterKey, and also to initialize an empty starting DB, according to the back-end in use (tables structures or containers). When running as daemon, its main purpose, the cache manager handles a set of queries coming from either the client library or remotely from another cache manager. Thereof, the most important is:

- Get a credential. Of a given resource for a given user (possibly running in a given environment or container). This query is only available locally. This is the main purpose of the system. The encrypted credential will be sent back, provided the access control gives the green light. Access control is based on the requester username, client hostname where the request comes from, and a validity time slot. If successful, then the credential, the user key and the ACL will be cached into memory for reuse. Unsuccessful queries are not cached, but non-granted credentials retrievals are. The size of the cache and its lifetime are configurable. It is a synchronous cache: the age of the data are only controlled at access time. It is also a dual layout cache: linear (full scan search) or BTree. The threshold level which decides when to pass from linear lookup to btree lookup is configurable and may even be determined automatically by the cache manager itself.

Some of these queries are cascadable: this means that the cache manager which received it, will forward it via UDP to all other registered cache managers.

Query client “cvquery”¶

This is the most important client of the CI. For retrieving the credential of a given user connecting to a given resource, optionally belonging to the container environment, the syntax will be following:

cvquery <user> <resource> [container]

The credential appears in stdout only if it is not connected to a terminal, otherwise the credential is not showed. Credentials retrieval can only occur through this client. ACLs are, between others, based upon the user running this utility and the host it is running on.

If a configuration file is parsed by the library fscan - part of cvault sources tree - then a directive:

passwd = cvault://user resource container

will be expanded by the result of the execution of cvquery with the corresponding arguments.

Considering the password “orapwd” of the user “oracle” for a resource “OraDB” running in a “TEST” environment, then the following command to connect would succeed:

$ sqlnet oracle/`cvquery oracle OraDB TEST`

The following however will fail:

$ cvquery oracle OraDB TEST

Crowdy refuse to prompt cleartext credentials. Use -f to force

Note that in the later case (i.e. with the -f switch), an extra newline is added to the password when prompted. To select the key to use other that the default one, use the switch -k:

$ cvquery -f -k 3 oracle OraDB TEST

orapwd

$

cvquery should also be used to expand any error or message code which are returned by the system. This is achieved with the switch -m. The numerical argument is signed, as illustrated in the following examples:

$ cvquery -m 5

CVERROR 5: Malformed query

$ cvquery -m -5

CVERROR -5: Socket type error for IP connection.

Control and management tool “cvctl”¶

The cvctl utility is the direct shell interface to the CI (targeting both Cache Manager and Admin daemons). It is the interactive part of the CI, and also the management utility. It will be used to start, stop the CI (or part of it). Without argument, it prints a help on (almost) all available features. To show a list of implemented and supported features in the client side, type cvctl --help.

The cache manager must run behind cvctl for all requests dealing with the DB (obviously), but also for all cryptographic related operations. Some features of cvctl may be sent to all registered servers simultaneously (or “cascaded”): this is enforced by using the switch -c.

This utility also allows to perform some administrative tasks by talking directly to the administrator daemon cvad. In the later case, the user must log into cvad with an administrator username. A default username can be provided in the configuration, and if this user exists in the DB, then the login process will first try to query the credentials of this administrative user from the cache manager. If this user is not registered or the previous credentials retrieval failed, then the admin daemon will proceed to a “manual” login with credentials provided in the command line (admin users must have been registered in a special file managed by cvad). We will detail later all of the capabilities of cvctl.

Swiss Army knife “cvtools”¶

This utility should simply NOT be part of the distribution, but from a recovery toolkit instead. It allows to perform all weird things against the CI such as encryption or decryption operations with plain text on the terminal, send any (good or bad) hand-crafted queries to the daemons, acting as an official client by hi-jacking its binary key, etc.

These features are only useful for deep investigation and debugging: it was the tool initially developed to perform the unit tests on each new version, for good conditions but for bad conditions as well (error generation).

In short, should one of the daemons crashes or presents funky behavior when “attacked” by cvtools, then we face a severe robustness quality problem in the code, which we want to fix asap...

Admin server “cvad”¶

This is the administrator daemon. It has connection to the local cache manager but also direct access to the backend credentials DB as well. To interact with it, the client must set a stateful session (client authentication, user login, admin tasks... , user logout, client disconnect). cvctl is the CLI client of choice, CvAdmin is the Java GUI client, and cvtools is the attacker’s client.